Global Economies

1. America is not in decline — it’s becoming more and more efficient

In 2009, while America was still gripped by the effects of the Great Recession, Berkshire Hathaway made one of its largest purchases ever: BNSF Railway Company.

He called it an “all-in wager on the economic future of the United States.”

While Buffett believes that other countries, particularly China, have very strong economic growth ahead of them, he is still bullish, above all, for his home turf of the United States.

Buffett, who was born in Omaha in 1930 and got his start in business working in his grandfather’s grocery store, is fond of making historical references in his annual shareholder letters. “Think back to December 6, 1941, October 18, 1987, and September 10, 2001″, he writes in his 2010 letter, “No matter how serene today may be, tomorrow is always uncertain.”

But, he adds, one should not take from any calamity the idea that America is in decline or at risk — life in America has improved dramatically just since his own birth, and is improving further everyday.

“Throughout my lifetime, politicians and pundits have constantly moaned about terrifying problems facing America. Yet our citizens now live an astonishing six times better than when I was born. The prophets of doom have overlooked the all-important factor that is certain: Human potential is far from exhausted, and the American system for unleashing that potential – a system that has worked wonders for over two centuries despite frequent interruptions for recessions and even a Civil War – remains alive and effective.”

The core of that success, for Buffett, is America’s particular blend of free markets and capitalism.

“The dynamism embedded in our market economy will continue to work its magic,” he wrote in 2014, “Gains won’t come in a smooth or uninterrupted manner; they never have. And we will regularly grumble about our government. But, most assuredly, America’s best days lie ahead… Americans have combined human ingenuity, a market system, a tide of talented and ambitious immigrants, and the rule of law to deliver abundance beyond any dreams of our forefathers.”

For Buffett, it is this mixture of system, mentality, and circumstance that has allowed “America’s economic magic” to remain “alive and well.”

Buffett’s belief in the American dream is so strong that he is willing to make huge, capital-intensive investments in companies like BNSF and BHE — companies that require large amounts of debt (of which Buffett is not fond) but which, so far, have generated high returns for the Berkshire Hathaway portfolio.

By 2016, BNSF and BHE combined made up 33% of all of Berkshire Hathaway’s yearly operating earnings.

“Each company has earning power that even under terrible economic conditions would far exceed its interest requirements,” he wrote that year, “Our confidence is justified both by our past experience and by the knowledge that society will forever need huge investments in both transportation and energy.”

Today, Buffett remains optimistic, despite the Covid-19 pandemic wreaking havoc across the world and parts of his business.

Berkshire reported an $11B write-down of its investment in the metal fabrication company Precision Castparts (PCC), as the pandemic brought aerospace manufacturing to a near halt, hurting some of PCC’s largest customers and pushing its shares down.

But Buffett is undeterred and boldly declares in his 2020 letter: “Never bet against America.”

18. Current board of director incentives are broken and backwards

Warren Buffett has a complicated relationship with boards. On the one hand, he has a long history of serving on them: according to his 2019 shareholder letter, he has served as a director on the board of a total of 21 publicly owned companies over 62 years.

On the other hand, he is deeply suspicious of what he sees as the modern-day trend of corporate boards incentivizing directors to be passive accomplices to whatever a CEO wants to do.

Boards aren’t all bad for Buffett. He identifies several recent promising changes in the culture around boards of directors, including the profusion of women on boards and the mandating of “CEO-free” sessions where executives can speak frankly.

But there is one big problem: the majority of CEOs aren’t actively looking for directors to challenge their decision-making.

Despite the fact that boards nominally seek directors with “independence,” the actual behavior of executives and other directors betrays this idea.

At the bottom of the problem is director compensation, which Buffett argues has “soared to a level that inevitably makes pay a subconscious factor affecting the behavior of many non-wealthy members.”

From 2013 to 2017, total director pay rose about 12%. Image source: Directors & Boards

Board directors are regularly paid more than $250,000 a year for the work of attending “six or so” annual meetings. They’re seldom fired, according to Buffett, and can generally serve well into their 70s. All of this adds up to a strong set of incentives to do whatever it takes to stay on the board. In most cases, that means never challenging their CEO.

Companies are eager to find these kinds of directors, Buffett says, but counterintuitively short-change those who have a large amount of their net worth tied up in the companies they serve. These directors, despite “possessing fortunes very substantially linked to the welfare of the corporation,” are ignored and deemed “lacking in independence.” Instead of being valued for the amount of skin they have in the game, they’re pushed aside. And the result is a set of incentives that isn’t good for companies, Buffett argues.

When directors have skin in the game, they’re more likely to look out for the company’s best interests. When you have directors who are in it for the money, you’re likely to get an absentee board, and worse outcomes.

“Not long ago, I looked at the proxy material of a large American company and found that eight directors had never purchased a share of the company’s stock using their own money. (They, of course, had received grants of stock as a supplement to their generous cash compensation.) This particular company had long been a laggard… But the directors were doing wonderfully,” Buffett writes.

Buffett is careful to not make a blanket statement here. “Paid-with-my-own-money ownership, of course, does not create wisdom or ensure business smarts,” he writes. Even directors who get salaries, he says, also tend to get grants of company shares. But Buffett argues that there is a fundamental difference between directors who put up their own money to intertwine their fate with that of the company they’re serving and directors who have simply “been the recipients of grants.”

Setting the question of incentives aside entirely, Buffett offers one final observation about directors to explain why he has complex feelings about boards and their current value.

While he’s confident that he admires many of the people he has served alongside on corporate boards, he says, there is one thing he feels less confident about: that he wants those people responsible for his money.

“Almost all of the directors I have met over the years have been decent, likable and intelligent,” he writes, “Nevertheless, many of these good souls are people whom I would never have chosen to handle money or business matters. It simply was not their game.”

Management

2. Embrace the virtue of sloth

Asked to imagine a “successful investor,” many would imagine someone who is hyperactive — constantly on the phone, completing deals, and networking.

Warren Buffett could not be farther from that image of the hustling networker. In fact, he is an advocate of a much more passive, 99% sloth-like approach to investing. For him, it is CEOs and shareholders’ constant action — buying and selling of stocks, hiring and firing of financial advisers — that creates losses.

“Long ago,” he wrote in his 2005 letter, “Sir Isaac Newton gave us three laws of motion, which were the work of genius. But Sir Isaac’s talents didn’t extend to investing: He lost a bundle in the South Sea Bubble, explaining later, ‘I can calculate the movement of the stars, but not the madness of men.’”

“If he had not been traumatized by this loss, Sir Isaac might well have gone on to discover the Fourth Law of Motion: For investors as a whole, returns decrease as motion increases,” he adds.

Buffett is a big advocate of inaction. In his 1996 letter, he explains why: almost every investor in the markets is better served by buying a few reliable stocks and holding on to them long-term rather than trying to time their buying and selling with market cycles.

“The art of investing in public companies successfully is little different from the art of successfully acquiring subsidiaries,” he writes, “In each case you simply want to acquire, at a sensible price, a business with excellent economics and able, honest management. Thereafter, you need only monitor whether these qualities are being preserved.”

“When carried out capably, an investment strategy of that type will often result in its practitioner owning a few securities that will come to represent a very large portion of his portfolio… To suggest that this investor should sell off portions of his most successful investments simply because they have come to dominate his portfolio is akin to suggesting that the Bulls trade Michael Jordan because he has become so important to the team,” he adds.

Buffett’s warning was a prescient one for retail investors who decided to take it. From 1997 to 2016, the average active stock investor only made about 4% returns annually, compared to 10% returns for the S&P 500 index as a whole. In other words, constantly buying and selling stock, and thinking that you can get an advantage from your instincts or analysis, has been proven to lead, in most cases, to smaller gains. And not just for your average retail investor.

“Lethargy bordering on sloth remains the cornerstone of our investment style,” Buffett wrote in his 1990 letter, and the difficulty of making any kind of money from buying and selling stocks is the very reason why. “Inactivity,” he adds, “strikes us an intelligent behavior.”

20. Time is the friend of the wonderful business, the enemy of the mediocre

By 1989, Warren Buffett was convinced that buying Berkshire Hathaway had been his first big mistake as an investor.

(By 2010, Buffett would say it was his biggest mistake ever — according to him, buying the company rather than insurance companies directly denied him returns of approximately $200B over the next 45 years.)

He bought Berkshire Hathaway because it was cheap. He knew that any temporary “hiccup” in the fortunes of the company would give him a good opportunity to offload the business for a profit.

The problem with that method, he reflects, is that mediocre companies (the kind that get offloaded for cheap in the first place) cost money in the time between you acquiring it and you selling it for a profit.

The approach of the more mature Buffett is to never invest in a company that can be a success if held for a short period of time. It is to only invest in companies that can succeed over an extremely long period of time, like 100 years or more.

“Time is the friend of the wonderful business, the enemy of the mediocre.”

No business that is not generating value over the long term is worth holding on to, and holding on to a bad business is never going to be a good investing strategy. This observation is important for Buffett, and for his overall conservative strategy in the market.

“The finding may seem unfair, but in both business and investments it is usually far more profitable to simply stick with the easy and obvious than it is to resolve the difficult,” he writes.

This philosophy extends to how Buffett thinks about finding managers.

“Our goal is to attract long-term owners who, at the time of purchase, have no timetable or price target for sale but plan instead to stay with us indefinitely,” he wrote in his 1988 letter, “We don’t understand the CEO who wants lots of stock activity, for that can be achieved only if many of his owners are constantly exiting. At what other organization — school, club, church, etc. — do leaders cheer when members leave?”

3. Complex financial instruments are dangerous liabilities

In 1998, Berkshire Hathaway purchased “General Re,” or the General Reinsurance Corporation.

In his 2008 letter, Buffett relates how he and Charlie Munger realized immediately that the business was going to be a problem.

General Re had been operating as a dealer in the swap and derivatives market, making money on futures, options on various foreign currencies and stock exchanges, credit default swaps, and other financial products.

While Buffett himself has professed to using derivatives at times to put certain investment and de-risking strategies into action, what he saw at General Re concerned him greatly.

General Re had 23,218 derivatives contracts with 884 separate counter-parties — a massive number of different contracts, most of which were with companies that neither Buffett nor Munger had ever heard of, and that they would never be able to untangle.

“I could have hired 15 of the smartest people, you know, math majors, PhD’s. I could have given them carte blanche to devise any reporting system that would enable me to get my mind around what exposure that I had, and it wouldn’t have worked,” he would later say.

It took Buffett and Munger 5 years and more than $400M in order to wind down General Re’s derivatives business, but they incurred those costs happily because they simply “could not get their minds around” a derivatives book of that size and complexity, and had no interest in owning a risky business they did not understand.

“Upon leaving,” he wrote, “Our feelings about the business mirrored a line in a country song: ‘I liked you better before I got to know you so well.’”

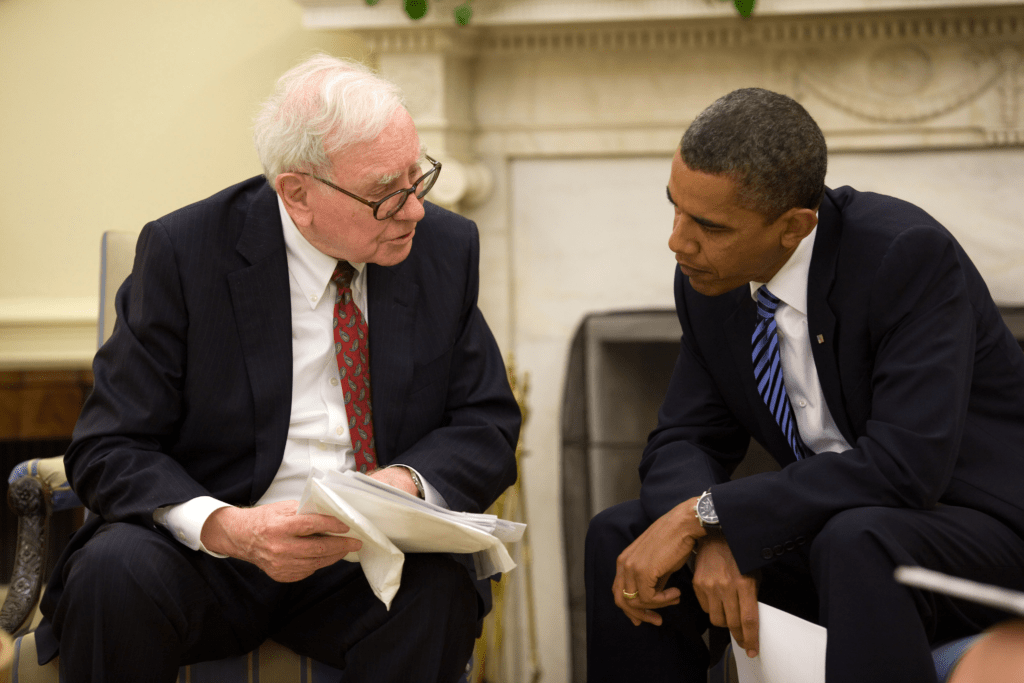

Warren Buffett with Barack Obama, whose administration pursued action to curb the use of complex financial derivatives in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis.

Buffett’s problem is less with the financial products themselves and more with the motivations behind using them to make a company’s quarterly numbers look better.

The reason that many CEOs use derivatives, Buffett says, is to hedge risks inherent to their business — like Burlington Northern (a railroad company) using fuel derivatives to protect its business model against an increase in the price of fuel.

A railroad like Burlington Northern might buy a futures contract, for example, that entitles them to buy fuel at a certain fixed price at a certain fixed point in the future. If the price of fuel stays the same or decreases, they still have to buy at the elevated price. However, if the price of fuel rises, they will be insulated from that increase and lower the damage to their business.

For Buffett, the problem with using derivatives to make money, rather than hedge bets, is twofold:

- Eventually, you’re going to lose just as much money on them as you win in the short term.

- Derivatives inevitably open up your business to incalculable amounts of risk.

Putting derivatives on your balance sheets always puts a volatile, unpredictable element into play. And it’s not one that can be fixed with regulation.

“Improved ‘transparency’ — a favorite remedy of politicians, commentators and financial regulators for averting future train wrecks — won’t cure the problems that derivatives pose. I know of no reporting mechanism that would come close to describing and measuring the risks in a huge and complex portfolio of derivatives,” he wrote.

“Auditors can’t audit these contracts, and regulators can’t regulate them,” he added.

4. Investment banker incentives are usually not your incentives

While Buffett and Berkshire Hathaway conduct plenty of business with investment banks and have invested in a few, he has issued some pointed criticisms at the industry over the years.

His main problem with investment bankers is that their financial incentive is always to encourage action (sales, acquisitions, and mergers) whether or not doing so is in the interest of the company initiating the action.

“Investment bankers, being paid as they are for action, constantly urge acquirers to pay 20% to 50% premiums over market price for publicly-held businesses. The bankers tell the buyer that the premium is justified for ‘control value’ and for the wonderful things that are going to happen once the acquirer’s CEO takes charge. (What acquisition-hungry manager will challenge that assertion?) A few years later, bankers — bearing straight faces — again appear and just as earnestly urge spinning off the earlier acquisition in order to ‘unlock shareholder value,’” he writes.

Sometimes this thirst for action even leads them to use fuzzy accounting to value the companies they’re selling.

His frustration with investment banker math reached its boiling point in his 1986 letter to shareholders, in which he dissected the value of Berkshire’s latest acquisition, the Scott Fetzer Company.

Buffett does not believe that standard GAAP accounting figures always give an accurate idea of what a company is worth, so he walks through a valuation of Scott Fetzer Company to explain why Berkshire purchased the company.

He wanted to show that typically, when one looks at a company through the lens of the earnings it will produce for its owners, the result is sobering relative to the company’s GAAP numbers — and that investment bankers and others use faulty numbers to push the companies they’re selling.

“All of this points up the absurdity of the ‘cash flow’ numbers that are often set forth in Wall Street reports. These numbers routinely include [earnings] plus [depreciation, amortization, etc.] — but do not subtract [capital expenditure and the cost of maintaining its competitive position].”

“Most sales brochures of investment bankers also feature deceptive presentations of this kind,” he adds. “These imply that the business being offered is the commercial counterpart of the Pyramids — forever state-of-the-art, never needing to be replaced, improved or refurbished. Indeed, if all U.S. corporations were to be offered simultaneously for sale through our leading investment bankers — and if the sales brochures describing them were to be believed — governmental projections of national plant and equipment spending would have to be slashed by 90%.”

For Buffett, investment bankers are too often simply using whatever math is most preferable for their preferred outcome, whether or not it is deceptive to the buyers and sellers involved in the transaction.

Culture

5. Leaders should live the way they want their employees to live

In his 2010 shareholder letter, Buffett provided a breakdown of all the money that is spent outfitting Berkshire’s “World Headquarters” in Omaha, Nebraska:

- Rent (annual): $270,212

- Equipment/supplies/food/etc: $301,363

By 2017, Berkshire Hathaway had hit about $1M in total annual overhead, according to the Omaha World-Herald — a paltry sum for a company with $223B in annual revenues.

The point of this breakdown is not to show off Berkshire’s decentralized structure, which offsets most operational costs to the businesses under the Berkshire umbrella, but to explain Berkshire’s culture of cost-consciousness. For Buffett, this culture must begin at the top.

Warren Buffett bought this house for $31,500 in 1958. It’s now worth an estimated $650,000. He still lives in it today. Image source: Smallbones

“Cultures self-propagate,” he writes, “Winston Churchill once said, ‘You shape your houses and then they shape you.’ That wisdom applies to businesses as well. Bureaucratic procedures beget more bureaucracy, and imperial corporate palaces induce imperious behavior… As long as Charlie and I treat your money as if it were our own, Berkshire’s managers are likely to be careful with it as well.”

For Buffett, there’s no reason for the CEOs of Berkshire’s companies to be careful with money if Charlie, him, and the inhabitants of Berkshire Hathaway’s HQ cannot be equally careful with it — so he insists on setting this culture from the top.

6. Hire people who have no need to work

In shareholder letter after shareholder letter, Buffett reminds his readers that the true stars of Berkshire Hathaway are not him or Charlie Munger — they are the managers that run the various companies under the Berkshire Hathaway umbrella.

“We possess a cadre of truly skilled managers who have an unusual commitment to their own operations and to Berkshire. Many of our CEOs are independently wealthy and work only because they love what they do… Because no one can offer them a job they would enjoy more, they can’t be lured away.”

Warren Buffett’s hiring strategy, as he explains it, is relatively simple: find people who love what they do and have no need for money, and then give them the most enjoyable job they could possibly have. Never force them into a meeting, or a phone call, or even a conversation — just let them work. It is to this strategy that Buffett credits much of the success of both Berkshire and its many companies.

“There are managers to whom I have not talked in the last year, while there is one with whom I talk almost daily,” he adds.

Berkshire Hathaway’s annual meeting, which no Berkshire CEO is required to attend. Image source: Stefan Krasowski

There’s very little that defines the kind of person that Buffett hires beyond these qualifications. “Some have MBAs; others never finished college,” he writes, “Some use budgets and are by-the-book types; others operate by the seat of their pants. Our team resembles a baseball squad composed of all-stars having vastly different batting styles… [changes] are seldom required.”

Whatever the mentality of the manager, the key is to give them the freedom in how to work and ensure that they get the most fulfillment out of it as possible, an ideal that Buffett sees as less of a science and more an art.

“Managers of this stripe cannot be ‘hired’ in the normal sense of the word. What we must do is provide a concert hall in which business artists of this class will wish to perform,” he writes.

7. Compensation committees have sent CEO pay out of control

In 2017, word got out that Yahoo CEO Marissa Mayer had been making a staggering $900K a week during her 5 years at the beleaguered company. This was a massive sum even by Silicon Valley standards, and many were shocked that someone with such a poor record made out so well.

Yahoo wasn’t doing well when she arrived, but many said her management style and decisions made it worse. She resigned in 2017 after the company was sold to Verizon.

Despite poor performance as CEO, Marissa Mayer made millions during her time at Yahoo, and walked away with a massive severance package after she resigned. Image source: World Economic Forum

CEOs didn’t use to command such enormous sums. Prior to World War I, the average annual salary of an executive at a large corporation was $9,958, or $220,000 in today’s dollars. Between 1936 and the mid-1970s the average CEO was paid about $1M a year in today’s money. By 2017, that average pay had ballooned to $18.9M, according to the Economic Policy Institute.

What happened?

Well, many things. But Buffett believes part of the answer lies with the compensation committees that determine the CEO’s pay package.

There’s often a cozy relationship between members and the CEO. Board members are well compensated, and if you want to be invited to serve on other boards, then making waves isn’t going to help. Buffett notes in his 2005 letter: “Though I have served as a director of twenty public companies, only one CEO has put me on his comp committee. Hmmmm . . .”

Buffett identifies the problem in the comparative data the committees use to determine a CEO’s compensation package. This has led to a rapid inflation in which the offers get bigger and more loaded with perks and payments. There’s little tied to performance.

“The drill is simple,” he wrote in 2005, “Three or so directors – not chosen by chance – are bombarded for a few hours before a board meeting with pay statistics that perpetually ratchet upwards. Additionally, the committee is told about new perks that other managers are receiving. In this manner, outlandish ‘goodies’ are showered upon CEOs simply because of a corporate version of the argument we all used when children: ‘But, Mom, all the other kids have one.’”

Debt

8. Never use borrowed money to buy stocks

If there’s a practice that infuriates Warren Buffett more than poorly structured executive compensation plans, it is going into debt to buy stocks or excessively finance acquisitions.

Much of Berkshire’s early success came down to the intelligent use of leverage on relatively cheap stocks, as a 2013 study from AQR Capital Management and Copenhagen Business School showed. But Buffett’s main problem is not with the concept of debt — it is with the type of high-interest, variable-rate debt that consumer investors must take on if they want to use it to buy stocks.

When ordinary people borrow money to buy stocks, they’re putting their livelihoods in the hands of a market whose swings can be random and violent, even when it comes to a reliable stock like Berkshire’s. In doing so, they risk potentially losing much more than their initial investment.

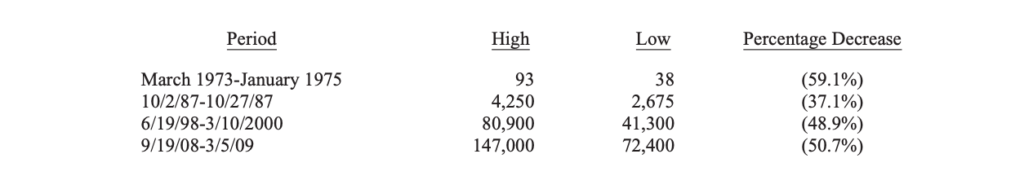

“For the last 53 years, [Berkshire] has built value by reinvesting its earnings and letting compound interest work its magic. Year by year, we have moved forward. Yet Berkshire shares have suffered four truly major dips.”

On four separate occasions, Berkshire’s stock fell by 37% or more within the span of just a few weeks.

“This table,” he writes, “Offers the strongest argument I can muster against ever using borrowed money to own stocks. There is simply no telling how far stocks can fall in a short period. Even if your borrowings are small and your positions aren’t immediately threatened by the plunging market, your mind may well become rattled by scary headlines and breathless commentary. And an unsettled mind will not make good decisions.”

When a stock falls by more than 37%, a highly leveraged investor stands a fair chance of incurring a margin call, where their broker calls and asks them to deposit more money in their account or risk having the rest of their securities portfolio liquidated to cover the losses.

“We believe it is insane to risk what you have and need in order to obtain what you don’t need,” Buffett writes. That’s why Buffett is a fan of some kinds of debt, just not the kind that can leave consumers broke when the market swings down.

9. Borrow money when it’s cheap

The Oracle of Omaha’s famous cost-consciousness does not mean that Berkshire Hathaway never borrowed money or went into debt — on the contrary, Buffett makes clear in his letters that he is enthusiastic about borrowing money in one type of circumstance.

Buffett is an advocate of borrowing money at a modest rate when he believes it is both “properly structured” and “of significant benefit to shareholders.” In reality, that usually means when economic conditions are tight and liabilities are expensive.

“We borrow… because we think that, over a period far shorter than the life of the loan, we will have many opportunities to put that money to good use,” Buffett writes, “The most attractive opportunities may present themselves at a time when credit is extremely expensive — or even unavailable. At such a time, we want to have plenty of financial firepower.”

When money is expensive, having more of it (in the form of debt) is a way of setting yourself up to take full advantage of opportunities. This fits nicely into Buffett’s general investment worldview that the best time to buy is when everyone is selling.

“Tight money conditions, which translate into high costs for liabilities, will create the best opportunities for acquisitions, and cheap money will cause assets to be bid to the sky. Our conclusion: Action on the liability side should sometimes be taken independent of any action on the asset side.”

10. RAISING DEBT IS LIKE PLAYING RUSSIAN ROULETTE

All across the business world, from big, corporate boardrooms to the offices of venture capitalists, managers employ the use of debt to juice returns. Whether it’s a company like Uber taking on $1.5B to re-energize its slowing growth or a startup like Cedar taking on $25M to find that initial growth curve, debt offers companies a way to acquire capital without giving up room on their cap table or diluting existing shares.

Debt also forces shareholders into a Russian roulette equation, according to Buffett in his 2018 letter. And “a Russian roulette equation — usually win, occasionally die — may make financial sense for someone who gets a piece of a company’s upside but does not share in its downside. But that strategy would be madness for Berkshire,” he writes.

Because of the incentive structure involved, the venture capital model where one great success of an investment can cover the losses of a hundred failures is especially prone to recommending the use of debt.

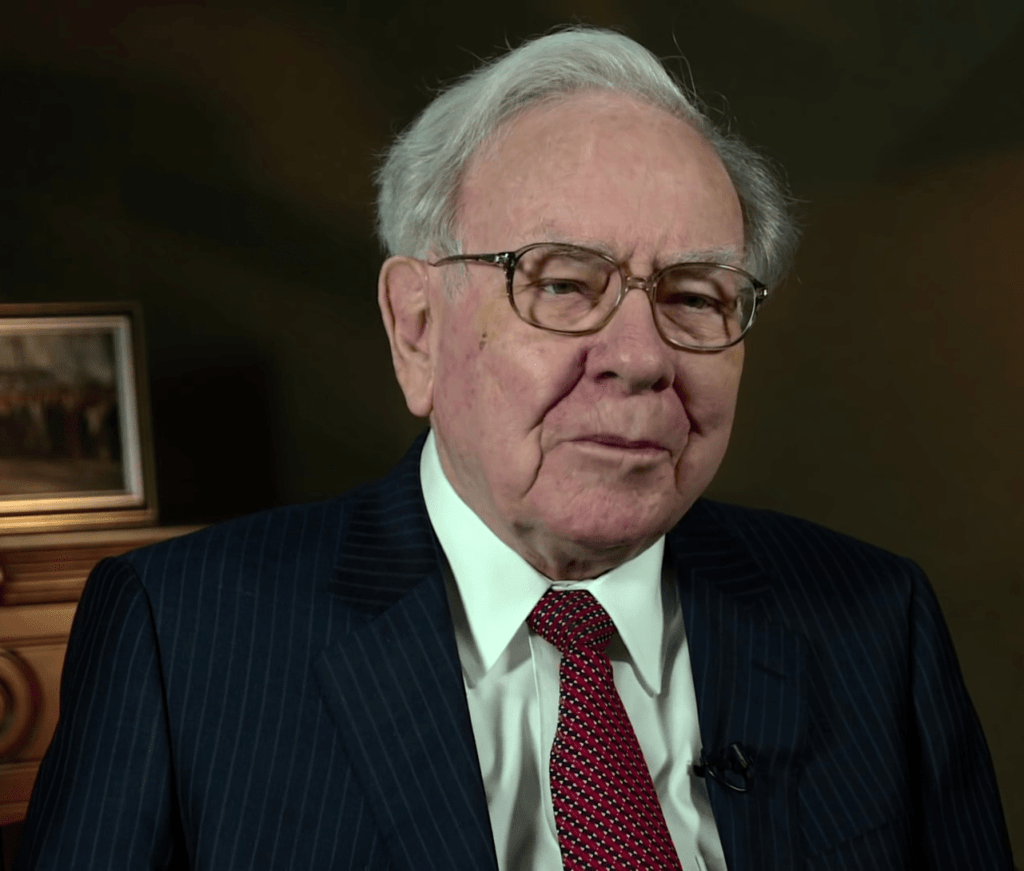

In his 2018 letter, Buffett announced that prices for companies were too high at the moment, and that Berkshire would continue to invest in securities while awaiting another “elephant-sized” opportunity. Image source: USA International Trade Association

A stock speculator is equally likely to promote the use of debt to increase returns because they can build out portfolios where they don’t have to worry about the downside risk. For them, it can make good sense to do so, since as Buffett points out, they’re usually not going to get a “bullet” when they pull the “trigger.”

For Buffett, however, who owns so many companies outright and intends to continue holding them for the long term, an outcome of “usually win, occasionally die” doesn’t make sense.

The risk of a company failing and a significant amount of debt getting called back is too great a risk, and Buffett and Berkshire Hathaway share in that risk equally with their shareholders.

Berkshire utilizes debt, but primarily through its railroad and utility subsidiaries. For these extremely asset-laden businesses that have constant equipment and capital needs, debt makes more sense, and they will generate plentiful amounts of cash for Berkshire Hathaway even in an economic downturn.

Source : https://www.cbinsights.com/research/buffett-berkshire-hathaway-shareholder-letters/

Leave a Reply